Dinohippus Leidyanus tooth

Dinohippus Leidyanus tooth

By: Ziv Carmi, Stratford Hall Summer 2020 Intern

Stratford Hall is famous as the historic home of the Lees. However, the land holds many more artifacts beyond those left by the Lees, the enslaved community, and its other human inhabitants. The cliffs at Stratford are geological treasure troves that hold many unique fossils (the petrified remnants of prehistoric organisms).

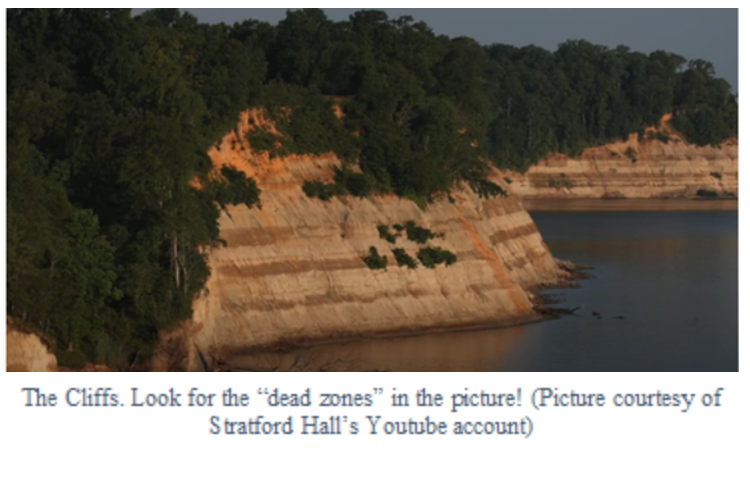

Stratford Hall has 2000 acres of ground and two and a half miles of riverfront. Looking at a picture of the cliffs, it is relatively easy to identify the different layers. Each darker line is a “dead zone” that was formed when the oceans transgressed, or rose further into the surface, and regressed back out. Indeed, according to Jon Bachman, Stratford Hall’s Education and Outreach Manager, at times, the ocean would have stretched all the way to Virginia’s I-95, putting Stratford Hall and the Cliffs entirely underwater.1 Every time the oceans moved across the Tidewater region, they would drop sediments and dirt, layering them until, over time, it became the rocky cliffs we all know and love today.

Looking downriver shows a different geology than looking upriver does, due to the unique geological formations of the cliffs. Looking in both directions shows the Calvert Formation, which consists of darker, grey clays and gummy sediments. This formation, the oldest and bottom-most layer found at the Cliffs, was created anywhere from 15 to 27 million years ago. There is a prevalence of marine fossils such as shellfish, snails, fish, and arthropods buried within this layer.2 Above the Calvert Formation is the approximately 14 to 10 million–year–old Choptank Formation, which is also evident both up and downriver. The sandier portion of the Choptank layer has many (although often poorly preserved) shells of clams, snails, and other invertebrates.3 These shell remnants, called “marl” by locals, are rich in calcium and phosphate and were mined for fertilizer in the late 19th century4. The vertebrate remains within the Choptank formation include shark and ray teeth, whales, sea turtles, and crocodiles.5 Of these, the crocodile fossils are especially interesting as they indicate a more tropical climate than today, about as tropical as Florida currently is, according to Jon Bachman.

The 11 to 8 million-year-old St. Mary’s formation is above the Choptank, and it has remains of freshwater animals but no mollusks.6 When the presence of freshwater vertebrates is combined with that of plants such as grasses, sedges, and other herbaceous species, it becomes evident that this area of the St. Mary’s formation was likely an estuary or a shallow bay.7 The St. Mary’s formation is very clear looking upriver, but looking downriver, it is only slightly present. Above the St. Mary’s formation looking upriver is the Bacon’s Castle formation. This 1.6 million-year-old formation is also not totally marine and shows indications of swamp deposits and brackish water. Indeed, it also has both fresh and saltwater fossils. Of note are remnants of 37 or 38 different mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish found in the layer, including the footprints of a short-faced bear and a giant ground sloth. This formation has a mixture of tropical, semi-tropical, and temperate animals, which indicates a variable climate during this period.

Looking downriver shows the Eastover formation above the small bit of the St. Mary’s. This formation, which, prior to 1980, was often considered to be a part of the St. Mary’s formation, is a lot sandier and younger than the St. Mary’s formation, about 5 million years old.8 A diverse array of specimens can be found from this layer, including sharks, rays, bony fish, whales, seals, land mammals, birds, and reptiles.9 These species are all far closer to modern forms than those found in the Calvert and Choptank, suggesting that the Eastover is significantly younger than those two layers.10 This idea is further supplemented by the law of superposition, an important geological and archaeological principle that says that the layer on the top is the youngest (if left undisturbed) due to the way sediment is deposited. Indeed, the Eastover formation is above the Calvert and Choptank formations and thus, by the law of superposition, is younger than both of them.

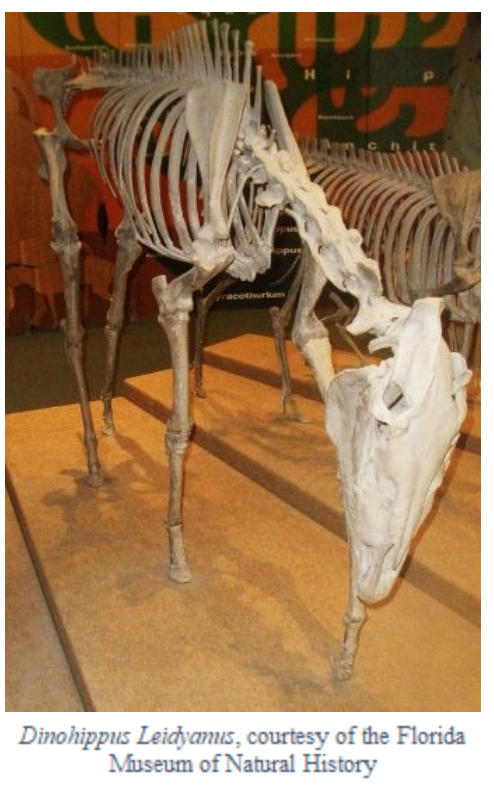

One of the most interesting finds in the Eastover formation is this tooth of a Dinohippus Leidyanus a relative of the horse. The tooth is about two inches long while a healthy modern horse has an average tooth size of anywhere from 3 to 4.5 inches. This size indicates a small animal compared to a modern horse, which is supported by other Dinohippus specimens found at different sites. Indeed, Dinohippus leg fossils are only about twenty inches tall, making Dinohippus about the size of an average pony if not smaller. Dinohippus fossils are found in the Upper Miocene epoch and date from 13 to 5 million years ago.11 The word “Miocene” means “less recent” and was created by Charles Lyell in 1828.12 This was a time period of much geological change, and a quarter of all animals living at that time are now extinct.13 624 Miocene epoch fossils have been found along the beaches of Stratford Hall and other adjacent shorelines14. Dinohippus appears to be the closest relative to Equus, the modern horse.15 According to Jon Bachman, this species lived in a forested environment, not the grassland which was developing as North America began drying out during this period. Dinohippus is unique in that it has a rudimentary form of the “stay apparatus”, the arrangement of bones and tendons that allow Equus to lock their limbs and sleep while standing up.16 They were likely one of the first species of horse to be able to sleep while standing up! Another unique thing about Dinohippus was that there was some variation in the number of toes found, suggesting that some specimens had three toes while others had only one.17

Paraphrasing Jon Bachman, when you find any intact fossil, it is a one in a million find, since, due to the process of fossilization and long timespan that fossils must remain intact, most specimens have been been eroded, eaten, or destroyed in some other manner. Indeed, of all life that paleontologists have discovered, it’s only about 5% of what was living at the time, and 95% of the species are lost to time. That is why places like Stratford Hall are so special. The unique geological structure at the Cliffs allows paleontologists to find many different fossils and reconstruct what life was like millions of years ago. Indeed, while Stratford Hall is thought by many to be a historic site, in terms of the knowledge we can gain from these fossils, it seems fair to call it a prehistoric site as well!

1“Rocks, Time & Fossils: Episode 3,” Stratford Hall, June 11, 2020, Video, 3:53, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0Yi3FFHZak&feature=youtu.be

2“Calvert Formation,” The Delaware Geological Survey, accessed June 9, 2020, https://www.dgs.udel.edu/category/geologic-units-and-aquifers/calvert-formation?page=1

3Robert E. Weems et al., “Geology and Biostratigraphy of the Potomac River Cliffs at Stratford Hall, Westmoreland County, Virginia,” The Geological Society of America, Field Guide 47 (2017): 139, https://doi.org/10.1130/2017.0047(05)

4Ibid.

5Ibid 143.

6Ibid 144.

7Ibid.

8Ibid.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

12 “Rocks, Time, and Fossils,” Stratford Hall.

13Ibid.

14Ibid.

15“Dinohippus,” Florida Museum.

16Ibid.

17Ibid.

Works Referenced

Florida Museum of Natural History. “Dinohippus.” Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/fossil-horses/gallery/dinohippus/

Godfrey, Stephen J. “The Geology and Vertebrate Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, USA.” Smithsonian Contributions to Paleontology, Number 100 (2018). https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo117196/107-27-3611-1-10-20181108.pdf

Stratford Hall. “Rocks, Time & Fossils: Episode 3.” June 11, 2020. Video, 3:53. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0Yi3FFHZak&feature=youtu.be

The Delaware Geological Survey. “Calvert Formation.” Accessed June 9, 2020. https://www.dgs.udel.edu/category/geologic-units-and-aquifers/calvert-formation?page=1

Weems, Robert E., Lucy E. Edwards, and Bryan Landacre. “Geology and Biostratigraphy of the Potomac River Cliffs at Stratford Hall, Westmoreland County, Virginia.” The Geological Society of America, Field Guide 47 (2017): 125-152. https://doi.org/10.1130/2017.0047(05)