Enslaved Africans and African Americans at Stratford Hall

Stratford Hall’s Role in Slavery and the Slave Trade

By the 18th century the transatlantic slave trade was in full throttle and captured African people were torn from their families and communities and sold into the Atlantic trade. Stratford Hall was home to generations of enslaved Africans and African Americans. Some of the enslaved community came from other Lee family sites, and others were brought directly from their West African homelands, or by way of the Caribbean colonies.

In 1738 the British slave trading ship, Liverpool Merchant, arrived on the Potomac after a voyage of 167 days and consigned 70 enslaved Africans, primarily from Senegambia, Gold Coast, and St. Helena Island, to Thomas Lee for sale to nearby plantation owners. Some of these enslaved laborers may have been purchased by Lee and tasked to build Stratford’s Great House and its dependencies. Their tasks would have included cooking meals, digging, and firing clay for bricks, and working as launderers, blacksmiths, plasterers, carpenters, and masons.

By the time Stratford was completed around 1742, an estimated 200 enslaved Africans and African Americans were living at Stratford and other properties owned by Thomas Lee. These men, women, and children were of diverse backgrounds, spoke different languages, and practiced different religions. They created new families, kinship bonds, married, loved each other, and did the best they could to create a sense of home.

This West African bead was excavated from the Oval site at Stratford Hall, dating to the early construction years (1738-40). It likely belonged to an enslaved African woman, who was part of the construction labor force. These beads were made in West Africa, and often worn around the wrists or waists of women, representing status and rights of passage.

Archaeology & Artifacts of Enslaved Communities

Through our archaeological research, we know these enslaved men, women, and children did not forget their cultural traditions, languages, or religious practices. Their memories helped them create new traditions and community and persevere through generations of captivity. Evidence of this is seen throughout Stratford Hall, our tours, archaeological collections, exhibits, and interpretation.

This first generation of enslaved Africans and African Americans at Stratford lived in temporary dwellings in an area now called the Oval Site, which has been the focus of several years of archaeological excavations.

From this site we have recovered objects that made it across the middle passage, such as a glass bead and a tortoiseshell and silver pipe. It is this first generation that also left behind extraordinary evidence of their cultural identities and religious practices through objects—an etched crystal and a conjuring cache—which enslaved individuals placed within the walls of the Great House. These objects and the stories associated with the enslaved community are now on display in the Visitor Center.

Stratford Hall and the Lee Family Were Dependent on Slave Labor

Enslaved Africans brought their culture and skills to Stratford Hall. Many of them would have known the art of blacksmithing and masonry, as well as sophisticated farming techniques. This knowledge was essential in the success of a working plantation. Enslaved people lived and worked throughout the plantation grounds. The field laborers slept in crowded quarters and worked sun-up to sun-down.

The enslaved community at Stratford Hall was also essential to the Lee family. Enslaved people worked the fields and served as domestics in the Great House, as postillions, maids, waiters, footmen, and cooks. Their labor allowed the Lees a lavish lifestyle. Those laboring in the domestic area resided in the house itself, as well as in the adjacent stone quarters, kitchen/laundry, and other outbuildings, and they were on-call 24 hours a day. Those who worked as cooks were skilled artisans, introducing the Lees and European indentured laborers to some of the dishes from West Africa.

Remembering Stratford Hall’s Enslaved Community

Some names of enslaved people who worked at Stratford are recorded in family documents, which allows us to interpret their lives more vividly, while the names and details of others have been lost in history.

Through archival and archaeological research and oral history, we are learning more about the lives of the enslaved community at Stratford Hall and are continually updating the tours and interpretation reflecting their history and legacy.

First Africans Day: Commemorating Stratford Hall’s Enslaved Africans and African Americans

An Annual Day Of Commemoration

First Africans Day was established in 2019 as an annual day-long event commemorating the enslaved Africans and African Americans who built and sustained Stratford Hall and the Lee family for generations. It is held in late July, near the date of the “first Africans” who arrived via the Liverpool Merchant in 1738.

Stratford Hall has a long history with African American descendant engagement. In 1929 when the Robert E. Lee Memorial Foundation purchased Stratford Hall from the Stuart family there were several descendants working on the site, specifically, the Payne family whose history at Stratford Hall dates back to the 18th century.

The Payne Family

With an oral tradition that their ancestors were enslaved by Thomas Lee, the Payne family’s history at Stratford Hall is as old as Stratford.

Very few records of the African and African American community at Stratford Hall exist, but it is possible that the Payne name originated with the Payne family that lived and are buried near the colonial port of Leedstown. It is also possible that the Paynes descended from an enslaved man named West who was listed in Philip Ludwell Lee’s estate inventory of 1782.

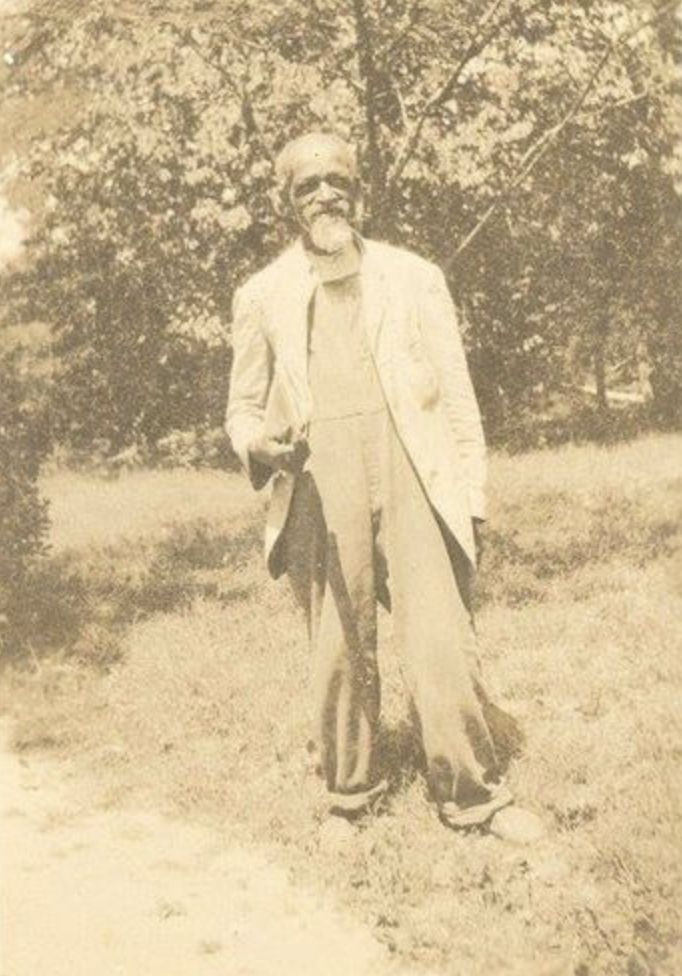

William “Bill” Payne

The first recorded Payne at Stratford Hall was William Payne (1833-1927) who was born on the plantation and worked, both before and after the Civil War, as butler and house servant for Mrs. Elizabeth Storke. He married Hannah Jackson from nearby Popes Creek Plantation. William’s brother Roderick Payne was Mrs. Storke’s driver. William “Bill” Payne is buried in the Shiloh Baptist Church cemetery, directly across from Stratford Hall’s entrance, and his wife Hannah is buried at Stratford Hall.

William Wesley “Wes” Payne

William Wesley “Wes” Payne (1875-1954), son of William and Hannah, grew up at Stratford Hall during Mrs. Storke’s ownership of the plantation. After Wes married Louisa Mary Johnson in 1901, she worked as cook for the Stuart family who inherited the plantation from Mrs. Storke. The couple made their first home in the outbuilding northeast of the Great House. Wes and Louise Payne had ten children! Wes (sometimes called West) worked at Stratford Hall for his entire life, except for four years after the death of his wife when he had to care for his youngest children. He is buried in Shiloh Baptist Church cemetery.

Ulysses Sylvester “Joe” Payne

Son of Willisam Wesley Payne and Louise Payne, Ulysses Sylvester “Joe” Payne (1909-1985) worked at Stratford Hall for fifty-three years. A veteran of World War II, Joe Payne began working for General and Mrs. B. F. Cheatham, Stratford Hall’s first resident superintendent, and served as Head Gardener for many years. He married Dorothy Johnson, who became a historic interpreter at Stratford Hall after her retirement from teaching school. Like his father and grandfather, Joe Payne is buried at Shiloh Baptist Church.

Thomas Payne

Thomas Payne, William Wesley Payne’s brother, also grew up at Stratford Hall.

Laura Payne

Laura Payne was one of Thomas Payne’s thirteen children, and Wesley Payne’s niece. Laura lived in the northwest brick room of the Great House while working as cook for the Stuart family from the late 1920s to 1932. After her marriage to Leon Streets, who worked on the farm at Stratford Hall, they lived in a tenant house that was moved to build the Executive Director’s house. In 1940 they built a home a short distance away on Route 3. Laura worked at Stratford Hall for 57 years, mostly as head cook in the Plantation Dining Room. Laura and Leon’s daughter, Vernell [Cruse], was born at Stratford Hall in 1936.

Known descendant family surnames:

Payne, Johnson, Lee, Whitlock, Johns, Jackson

Known Payne family members buried in the African American cemetery at Stratford Hall

Walter Payne (Wesley Payne’s uncle); Hannah Jackson Payne (Wesley Payne’s mother); Ardrick Payne (Wesley Payne’s brother); Lawrence Payne (Wesley Payne’s brother); Ardrick Payne (Wesley Payne’s great-uncle); William Payne (Wesley Payne’s great-uncle); Walter Payne (Wesley Payne’s great-uncle) and Hannah Payne (Wesley Payne’s sister).

Wesley Payne Birthplace Memorial

Wesley “Wes” Payne is best remembered for his lively interpretation of the kitchen yard after the Robert E. Lee Memorial Foundation purchased Stratford Hall in 1929.

During this period, in an early example of descendant engagement, Mrs. Lanier, President of the Foundation, offered Wesley Payne his choice of a monument marking his birth site. He preferred that a cabin, similar to the one in which he was born, be built on the knoll across from the Great House.

The cabin, built to Wesley’s description, was constructed in 1941 in honor of his family.

Today we are honored to have Denise Smith, a Johnson/Payne family descendant, working with us as the African American Descendant Coordinator. Ms. Smith has helped expand the descendant engagement to include additional families whose ancestors left the area generations ago. We welcome the descendants to visit and be a part of telling their history at Stratford Hall.

Stratford Hall Descendant Engagement & Coordination

Today we are honored to have Denise Smith, a Johnson/Payne family descendant, working with us as the African American Descendant Coordinator. Ms. Smith has helped expand descendant engagement at Stratford Hall to include additional families whose ancestors left the area generations ago.

We welcome the descendants to visit and be a part of telling their history at Stratford Hall.

Are you a descendant of an enslaved person or family at Stratford Hall? Please reach out to Denise Smith our African American Descendant Coordinator. We welcome you to visit and be part of telling your family’s story.

For more information contact:

Ms. Denise Smith, African American Descendant Coordinator

Dr. Gordon Blaine Steffey, Director of Research and the Jessie Ball duPont Memorial Library