The Mysteries of Museum Collections

The Mysteries of Museum Collections

By: Ziv Carmi, Stratford Hall Summer 2020 Intern

Museums might not know everything about an artifact in their collection. However, these collections are excellent resources for researchers to use to uncover more answers about our past. Indeed, these statements hold especially true in the case of this flag, which reportedly belonged to Revolutionary War hero, Light Horse Harry Lee.

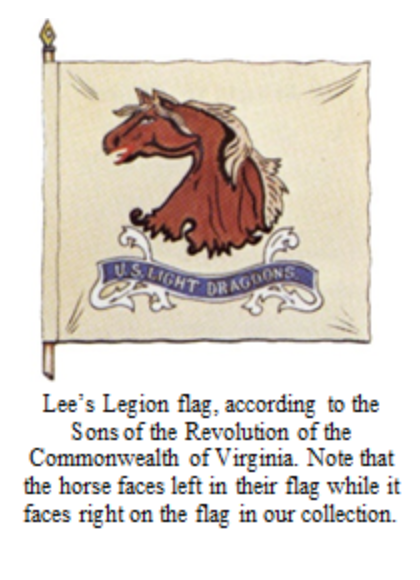

The flag, which was purchased by the Robert E. Lee Memorial Foundation from Francis Bannerman & Sons in 1947, consists of a brown horse facing right with the words “U.S. Light Dragoons” on a ribbon below it. It is 2’4” wide and 4’11” long. To compare, the usual size of flags flown at homes are 3’ wide and 5’ long.1 According to the Sons of the Revolution of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the flag was smaller than some other regimental flags for mobility purposes and ease of use while on horseback. Indeed, compared to a flag flown at the Battle of Monmouth that is 4’8.75” wide and 5’4” long, this flag is about half as wide (but almost as long)!2

The flag was sewn from silk, while silk may seem like an unusual choice for a fabric, it is not unique to this artifact. According to Barbara Gatewood, professor emeritus of textile science at Kansas State University, early American flags were usually made from either wool, cotton, linen, or silk, but due to silk’s high price it was used in flags for military purposes and special occasions rather than everyday use.3

The preservation of this flag is necessary, given its poor condition and fading coloration. It was first mounted, folded, and sealed in a case measuring 26” by 26” by the US National Archives in 1948. It was remounted in 1983 for exhibition, and was on display at Stratford Hall until 2009, when it was removed the permanent exhibit for preservation reasons.4 Indeed, light not only fades the coloring of textiles such as this flag, but also causes the fabric to deteriorate. In fact, ultraviolet radiation has energy to break the molecular bonds within the silk fibers.5 This damaging effect of light is why many museum exhibits, including the Star-Spangled Banner exhibit in the Smithsonian American History Museum, are so dimly lit.

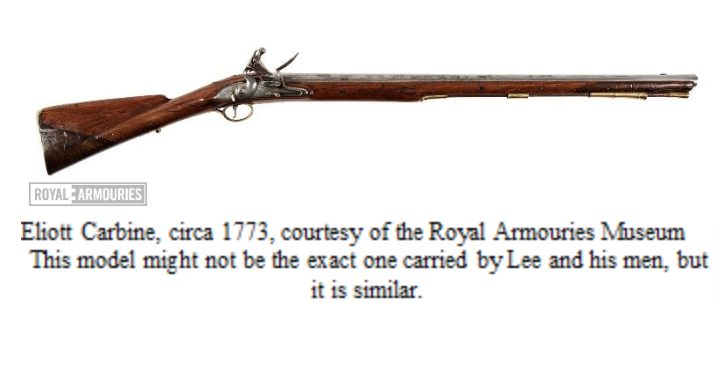

This flag was the standard of the 2nd Partisan Corps, also known as Lee’s Legion. Lee commanded a dragoons regiment, a medium cavalry force. While light cavalry was mainly used for reconnaissance and heavy cavalry fought mainly on horseback, dragoons rode into battle and then dismounted, fighting mainly on foot, although they were trained to fight on horseback as well.7 The name “dragoon” comes from a nickname for the carbine, their weapon of choice. A carbine is a smaller weapon with a shorter barrel than a musket, built to be lightweight and thus allow for soldiers on horseback to travel quickly. Carbines were designed to be used defensively when the soldiers were dismounted and were very inaccurate when fired on horseback because of their short barrels (about 20 inches long).8 They emitted a burst of fire when shot, giving them the common moniker of “dragon”, a nickname that ultimately evolved to become the name of the troops who carried them.

Lee’s Light Dragoons Regiment was formed at Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia Colony at the time, on June 8, 1776, as the 5th Troop of Light Horse of the Virginia State Troops.9 Later that summer, it was incorporated into the Continental Army, and by November of 1776, assigned to the 1st Continental Light Dragoons under Colonel Theodoric Bland’s command.10 Bland’s command, including Light Horse Harry and his men, participated in the Battle of Brandywine, scouting positions of British troops but not actually engaging in any combat. The division was withdrawn from Bland’s regiment on April 7, 1778, when Lee was promoted to Major and given command of the 2nd Partisan Corps.11 Once the 2nd Partisan Corps was formed, Lee held command over about 100 cavalry and 180 foot soldiers.12 The Legion is famous for being well clothed and equipped, a quality attributed to Lee’s persistence and determination to have a command that was so.13 Lee mentions in his memoirs that the cavalrymen wore “green coatees and leather breeches”, and on several different occasions, were confused with Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers and Tarleton’s British Legions (two prominent British commands) due to all three troops wearing similar green jackets.14 However, supply records show that some of the members of the unit wore blue coats with red trim, leather caps, visored black or brown leather helmets, and occasionally, a felt hat.15 This inconsistency likely occurred because, despite the good condition of dress in the Legion, clothing was often hard to come by. Indeed, the Legion infantry has been described wearing purple trousers and jackets earlier in the war and scarlet and blue uniforms later in their service.16

Lee and his men had several triumphs during the Revolution, including at the Battle of Germantown, where they served as Washington’s bodyguards and the Battle of Paulus Hook, where Lee took over a hundred British soldiers as prisoners of war with very few Patriot casualties17. Indeed, his success at Paulus Hook earned Lee a gold medal from the Continental Congress, an award not given to any other officers below the rank of general, and his actions were described as a “remarkable degree of prudence, address and bravery” by Washington.18 Following his successes in the Middle Colonies, Lee, now promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, participated in the Southern Campaign, where, at the Battle of Haw River (also known as Pyle’s Defeat), he and his dragoons killed almost 100 Loyalist soldiers without losing a single man.19 Lee’s Legion also saw action at the Battle of Guilford Court House, Siege of Ninety-Six, and Battle of Eutaw Springs before moving to Yorktown, where Lee was an eyewitness to Cornwallis’ surrender.20 By early 1782, Lee had resigned from command, and, on November 15, 1783, the unit formally disbanded.21

The flag’s history is the largest mystery about this object. Since the term “US Light Dragoons” indicates use after the Revolutionary War (the first U.S. Dragoons troop formed in 1792 and saw action in the War of 1812), the flag’s origins remain unknown. According to the Sons of the Revolution of the Commonwealth of Virginia, who display a very similar flag in their gallery, the flag was first carried in the Southern Campaign in 1781 and used until after Yorktown in 1782.22 Since the flags are so similar in appearance, it would be a fair assumption to say that the flag in Stratford Hall’s collection likely dates circa the same time period. However, the object’s alleged history creates many more questions; it is said to have belonged to Lee and been flown during the battles of Monmouth, Bemis Heights, Bennington, Saratoga, and Germantown. Of these battles, we know from documentary evidence that Lee and his troops were at Germantown (the outskirts of Philadelphia) as Washington’s bodyguard, but they were not at Saratoga or Monmouth, which raises more questions about the origin of this flag’s background. Furthermore, the term “legion” in the 18th century referred to commands consisting of men both on foot and on horseback. Prior to the formation of Lee’s Partisan Corps in April 1778, Lee and his men were in a light dragoons’ division rather than a legion. Since a similar flag was purportedly carried by Lee’s Legion (according to the Sons of the Revolution), this flag might not have been used prior to its formation in 1778, which further brings its history into question since it might not have been used at Germantown in 1777. These questions, of course, require significant more research to answer, but that is one of the most fun parts about a museum’s collection.

While museums may not always hold all the answers, their collections often are some of the best resources for answering the questions of the past. Oftentimes, research can only create more questions, like in this case. However, that is part of the joys of working in museum and artifact culture. While we may never know everything, every single discovery made during the research process and every little piece of the puzzle connected is exhilarating, and it is incredibly gratifying to get any glimpse into the past, even the smallest ones.

1“Flagpoles, Flag Sizes, Flag Proportions,” Independence Hall Association, accessed June 5, 2020, https://www.ushistory.org/betsy/flagetiq3.html

2Monmouth County Historical Association, “Monmouth Flag,” Accessed June 17, 2020, https://monmouthhistory.emuseum.com/objects/733/monmouth-flag

3Stephanie Murray, “Long May it Wave: As America Changed, so did the Fabric of its Flag, Expert Says,” K-State News, 7/1/2013, https://www.k-state.edu/media/newsreleases/jul13/flaghistory7113.html

4Stratford Hall, “Flag, Silk and linen, c. 1780s… Behind the Scenes,” Facebook, September 28, 2010, https://www.facebook.com/StratfordHall/photos/a.333410640577/10150279975055578/?type=3

5“Deterioration,” Western Australian Museum, accessed June 5, 2020, https://manual.museum.wa.gov.au/conservation-and-care-collections-2017/textiles/deterioration\

6Stratford Hall, “Flag.”

7“Dragoon Soldier- Historical Background,” Fort Scott National Historic Site, accessed June 1, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/education/dragoon5.htm

8Ibid.

9“Cavalry Carbine,” Waterloo 200, Age of Revolution, accessed June 2, 2020, https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/firearms-of-british-cavalry-soldier/

10 Sherman, William T., “Lee’s Legion Remembered,” accessed June 1, 2020:2, https://www.americanrevolution.org/leeslegion.pdf

11Ibid.

12Ibid 3.

13Ibid.

14Ibid.

15Ibid 3-4.

16Ibid 4.

17“Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee III,” American Battlefield Trust, accessed June 1, 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/henry-lee-iii

18Ibid.

19Ibid.

20Ibid.

21Sherman, “Remembering Lee’s Legion,” 4.

22“Light Horse Harry Lee’s Light Dragoons Guidon,” Sons of the Revolution of the Commonwealth of Virginia, accessed June 1, 2020, http://srvirginia.org/light-horse-harry-lees-light-dragoons-guidon/

Works Referenced

American Battlefield Trust. “Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee III.” Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/henry-lee-iii

Fort Scott National Historic Site. “Dragoon Soldier- Historical Background.” Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/education/dragoon5.htm

Independence Hall Association. “Flagpoles, Flag Sizes, Flag Proportions.” Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www.ushistory.org/betsy/flagetiq3.html

Monmouth County Historical Association. “Monmouth Flag.” Accessed June 17, 2020. https://monmouthhistory.emuseum.com/objects/733/monmouth-flag

Murray, Stephanie. “Long May it Wave: As America Changed, so did the Fabric of its Flag, Expert Says.” K-State News, 7/1/2013. https://www.k-state.edu/media/newsreleases/jul13/flaghistory7113.html

Sherman, William T. “Lee’s Legion Remembered.” Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.americanrevolution.org/leeslegion.pdf

Sons of the Revolution of the Commonwealth of Virginia. “Light Horse Harry Lee’s Light Dragoons Guidon.” Accessed June 1, 2020. http://srvirginia.org/light-horse-harry-lees-light-dragoons-guidon/

Stratford Hall. “Flag, Silk and linen, c. 1780s… Behind the Scenes.” Facebook, September 28, 2010. https://www.facebook.com/StratfordHall/photos/a.333410640577/10150279975055578/?type=3

Traynor, Lisa, Royal Armouries Museum. “Eliott Carbine.” Accessed June 5, 2020. https://collections.royalarmouries.org/battle-of-waterloo/arms-and-armour/type/rac-narrative-532.html

Valley Forge National Historic Park. “Shoulder Arms of the American Revolution.” Accessed June 3, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/upload/Muskets-and-Rifles-with-arrowhead.pdf

Waterloo 200, Age of Revolution. “Cavalry Carbine.” Accessed June 2, 2020. https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/firearms-of-british-cavalry-soldier/

Western Australian Museum. “Deterioration.” Accessed June 5, 2020. https://manual.museum.wa.gov.au/conservation-and-care-collections-2017/textiles/deterioration\